Identification – flint, fossil sponge

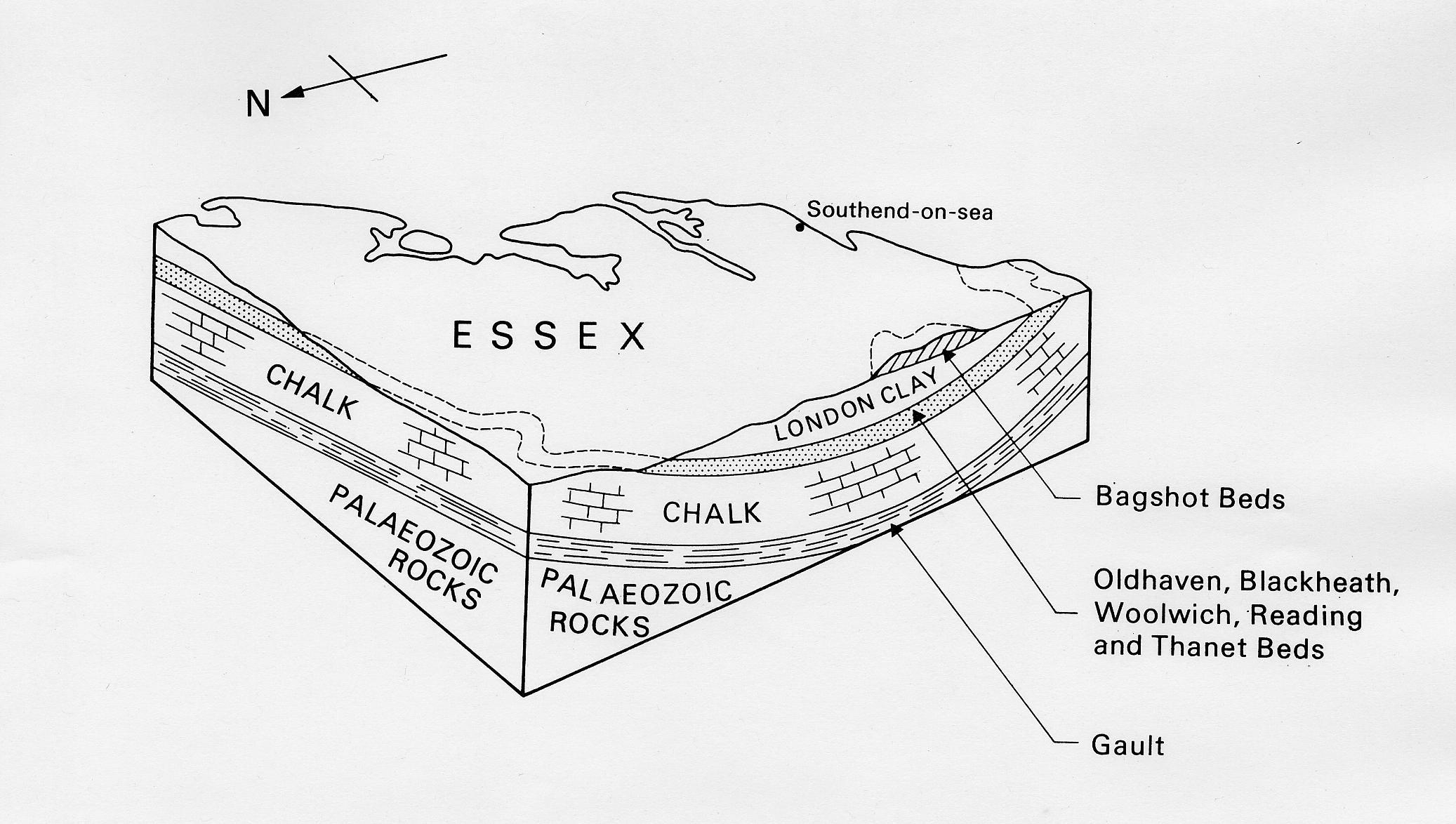

In Essex and south east England, almost every pebble on the beach and in gardens is flint. It’s a hard rock found in the Chalk, a soft, white, limestone layer that is up to 200m (600 ft) thick in north Essex and Cambridgeshire. In north west Essex, this chalk is between 90 million and 66 million years old and lies just below the soil, north of a line running from Stansted to Sudbury.

Diagram showing the main bedrocks across a section of Essex. Chalk appears as the bedrock across northern Essex. Credit: reference 1.

Chalk started out as a thick mud on the floor of a tropical sea that covered most of Britain and north west Europe. This mud contained the remains of tiny sea creatures (plankton) which grew shells of calcium carbonate. When they died, these plankton and their shells fell to the sea floor to form a thick mud, which compacted into chalk over millions of years.

As it compacted, it squeezed out the seawater containing dissolved quartz, or silica (which comes from the skeletons of tiny sponges, a very simple animal).This silica was pushed out into gaps, cracks and burrows in the chalky mud to form nodules or layers of flint. These flints have a white outer layer (cortex), and are black inside. They can come in very complicated, bulging shapes, or with spikes, holes and cavities. Because of this, they can be easily confused with fossilised bones.

An irregular flint nodule with a white cortex. Credit: reference 2.

Some flints do contain fossils, often urchins, or cockles or other small shellfish. Sometimes, the whole flint looks like fossil, and this may be because the silica that created it was forced into a hollow space in the hardening chalk which contained a sponge. Sponges are very simple animals which live on the sea floor. They still exist today, and the earliest known fossil sponges are 580 million years old.

The silica fills the gaps in the sponge’s skeleton and, over millions of years, the skeleton itself can dissolve away and be replaced by other minerals. This skeleton is a fossil, and the flint fills the spaces left by the soft parts of the animal after they rotted away.

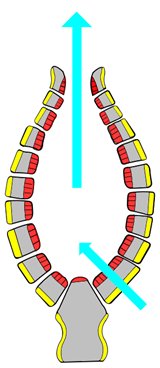

Sponges are hollow tube or cone shapes and have no muscles, stomach, brain or nerves. They are filter feeders that catch bacteria and microscopic plants & animals from seawater that flows through tiny channels (pores) in their body. Sponges are open at the top, and water currents flowing across the opening helps pull in water through the pores and remove it from the centre chamber, like wind blowing across a chimney.

A simple diagram of a sponge’s body showing the pores in the sponge’s body, and the direction of water flow (blue arrows). Credit: reference 3.

A living sponge, showing the typical hollow tube shape. Credit: reference 4.

The first sponge below is preserved in chalk and is a typical funnel shape. Some fossils may have a textured ring around the top, showing the rough pattern of the sponge’s surface and pores, like in the second photo.

Fossil of a sponge (Ventriculites species) that lived in the Chalk sea. This sponge attached to the sediment with its branching roots. © SWM.

A flint nodule showing the imprint of the upper rim of a sponge’s body. Credit: reference 5

References

- Essex Bedrock, Essex Rock 1999. GeoEssex.org, retrieved 11:36, 24.4.2020

- © G Lucy. GeoEssex.org, retrieved 11:31, 24.4.2020

- Adapted from: Porifera_body_structures_01 By Philcha – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

- NOAA Photo Library reef3859 By Twilight Zone Expedition Team 2007, NOAA-OE. , Public Domain,

- Flint rim print. flint-paramoudra.com, retrieved 11:47, 24.4.2020