Tag Archive for: Archaeology

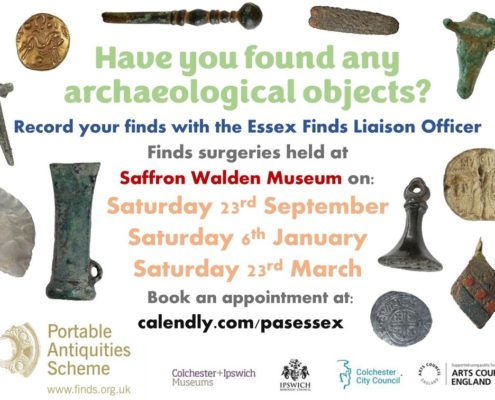

Archaeological Finds Surgery, Saturday 6th January 2024

Book an appointment for the archaeological finds surgery being…

Object of the Month – November 2023

The Museum’s ‘Object of the Month’ provides an opportunity…

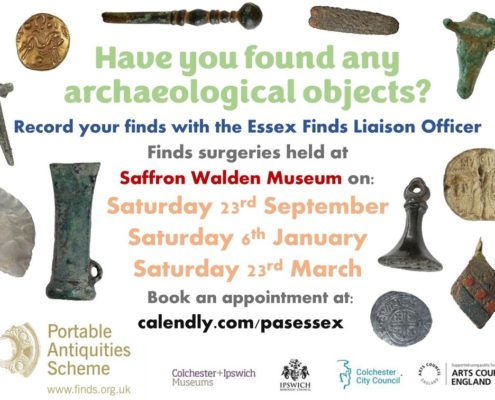

Essex Finds Liaison Surgeries

Essex Finds Liaison Surgeries at Saffron Walden Museum -…

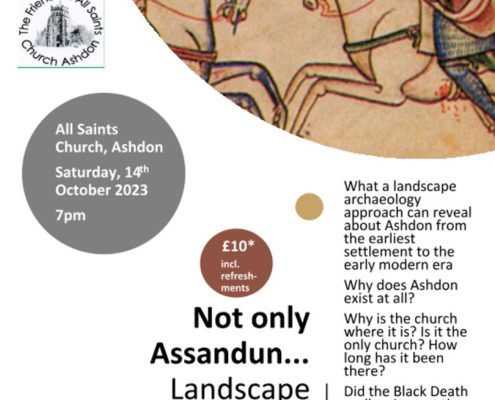

Landscape Archaeology in Ashdon talk

Simon Coxall, Landscape Archaeologist talk at the…

Object of the Month – July 2023

The Museum’s ‘Object of the Month’ provides an opportunity…

Object of the Month – November 2022

The Museum’s ‘Object of the Month’ provides an opportunity…

Object of the Month – July 2022

The Museum’s ‘Object of the Month’ provides an opportunity…

The Hadstock ‘Daneskin’ – new research on an old mystery

One of the exciting research projects to involve Museum collections…

Tag Archive for: Archaeology

Essex Finds Liaison Surgeries

Essex Finds Liaison Surgeries at Saffron Walden Museum –…