Tag Archive for: chalk

Identification – Fossil sponge in flint

Some flints do contain fossils, or look like whole fossils. Fossils…

Identification – Sea urchin fossil

Did you know we identify items for free? Whether it's a rock…

Identification – flint, fossil sponge

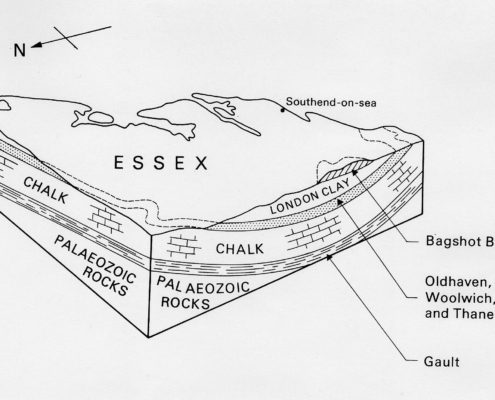

In Essex and south east England, almost every pebble on the beach…

Object of the Month -September 2018

September’s Object of the Month is a collection of fossilised…