Tag Archive for: saffron walden

Object of the Month – June 2023

This is the cast skin / exoskeleton (exuvia) of a dragonfly larva,…

Object of the Month – June 2022

June’s object of the month celebrates the Lost Language of…

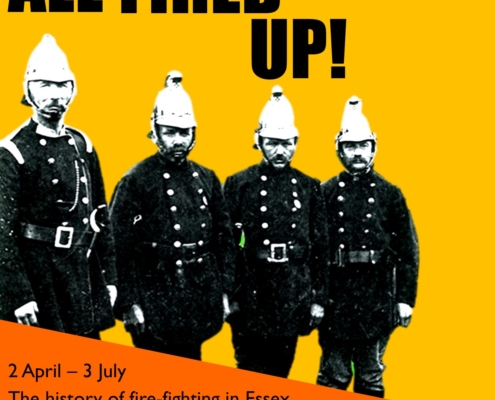

New Special Exhibition – All Fired Up!

Essex Fire Museum and Saffron Walden Museum have collaborated…